Quick Start

This section describes structured topic-based authoring in Paligo.

If you are completely new to topic-based authoring, it might be a bit confusing to know exactly what you are supposed to do to create your content. This chapter will give you the basics.

The first important thing to know is that you don't write your publication as one big document, as you might have done in MS Word or other traditional authoring tools. Instead, you create small "topics" or building blocks of content and reuse them in a publication. To learn more, see Content Reuse vs Copying.

|

Go through these videos and you'll soon get the hang of it!

Structured content is information that is organized and categorized based on a set of rules. In Paligo, these rules are defined by a customized version of the DocBook content model, which is a well-established standard for technical documentation. All of the content you create in Paligo is validated against the rules defined in the content model.

In Paligo, the structure consists of:

|

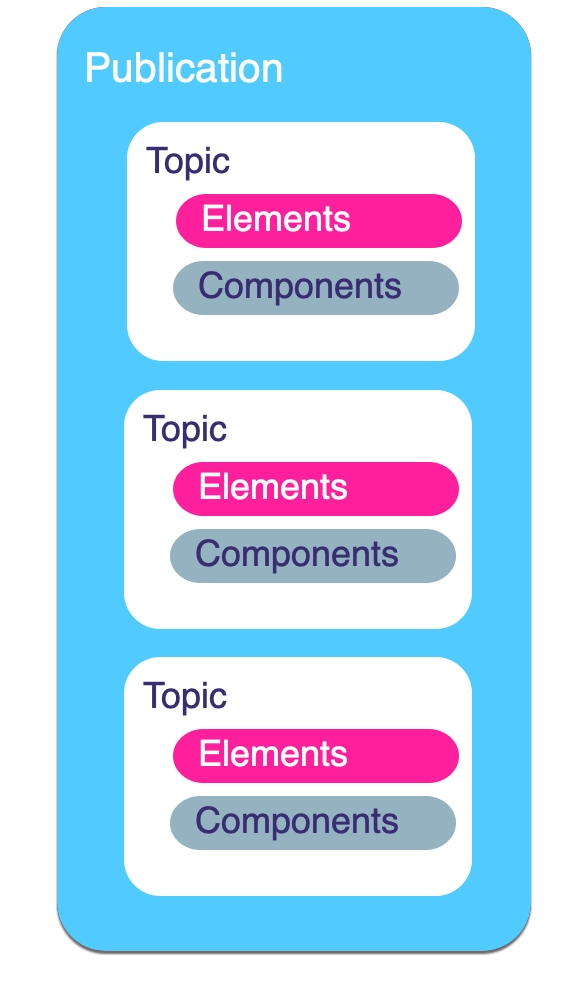

Publication

A publication represents the entire document that you want to publish, such as a user guide or a help center. Its structure contains references to all of the sections (topics) that you are going to include in the document.

Topics

You write each section of your content inside a “container” called a topic.

Elements

Inside each topic, you need to add the structure for your content as well as the actual text, images, etc. You make the structure by adding elements. There are different elements for each type of content, for example, a

paraelement for paragraphs and anitemizedlistfor a bullet list.The elements are defined by a content model that is based on DocBook.

Note

The block elements are hierarchical, which is especially important when moving content and applying filters. When you move a “parent” element, its “child” elements move with it. Similarly, if you use filters to exclude a “parent” element then its “child” elements will also not appear.

Components

If you want to reuse some of the content inside a topic in other topics, use components. You create the content in a component, which is a separate container, and then you can insert that into as many topics as you like. A common example is a note. You can create a note as a separate component and then insert that note into many different topics.

The content you add in a component also has to have elements for the structure and must follow the rules of DocBook.

The idea is that you build your content from modules of information, like a hierarchy of "building blocks":

To build a topic, you use elements and components as your building blocks.

To build a component, you use elements as your building blocks.

To build a publication, you use topics as your building blocks.

To learn more about structured content for each type of "building block", see:

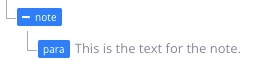

When you create structured content in Paligo, there is a hierarchy that is made up of “Parent” elements and “Child” elements. The parent elements are at a higher level, and the child elements are nested inside them. For example, here is a simple note structure, where note is the parent element and para is the child element.

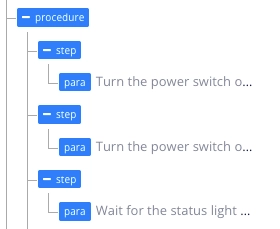

As you build your content, you will likely use more complex structures, where some child elements are also parents to other descendant elements. For example, with a procedure, the procedure element is a parent to the step elements. But each child step element is also a parent, because it has a child para element for the text.

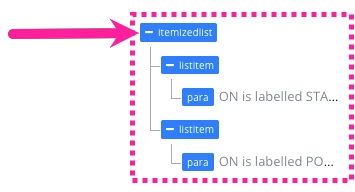

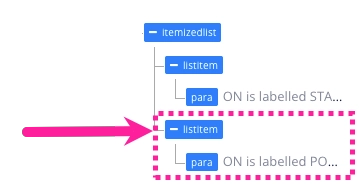

It is important that you understand the parent-child relationships and the hierarchical nature of the structure. Because any time you move, copy, or delete a parent element, that action also applies to the child elements inside it. For example, if you move an itemizedlist, you also move its listitems and the child elements inside those.

But if you only copy, move, or delete a child, the action only applies to the child (and any of its children). The action does not apply to the parent.

This hierarchical "parent-child" structure has some useful advantages for technical writers—it means you can move, copy, and delete entire structures at once, rather than having to manage them separately. It is especially useful with more complex structures, such as lists, as it can make it much easier to change the list order, move content, etc. The following example shows the parent-child relationships in a procedure and how moving a step affects the structure.

Tip

If you are unsure about the hierarchy of elements and how the parent-child relationships work, create a test topic and experiment with it. We recommend that you add a mix of regular paragraphs and more complex structures like lists and tables and then try copying, moving, and deleting the parent and child elements.

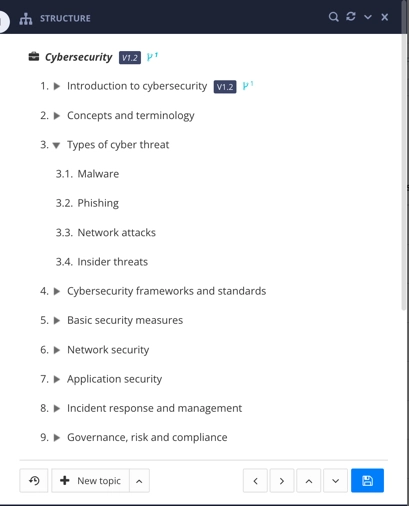

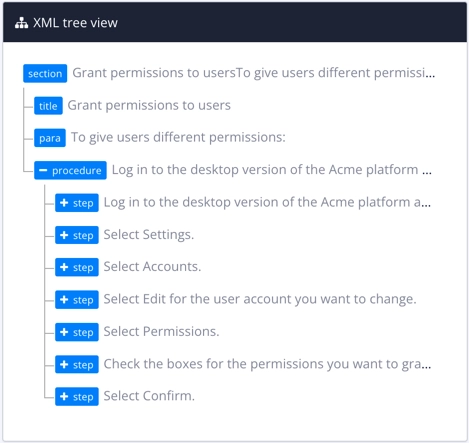

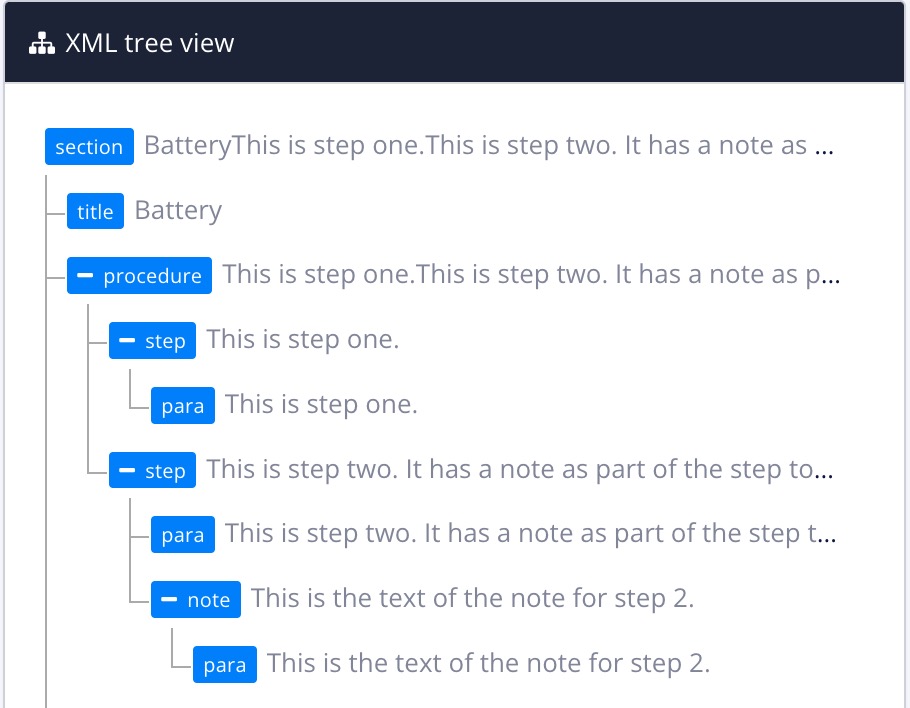

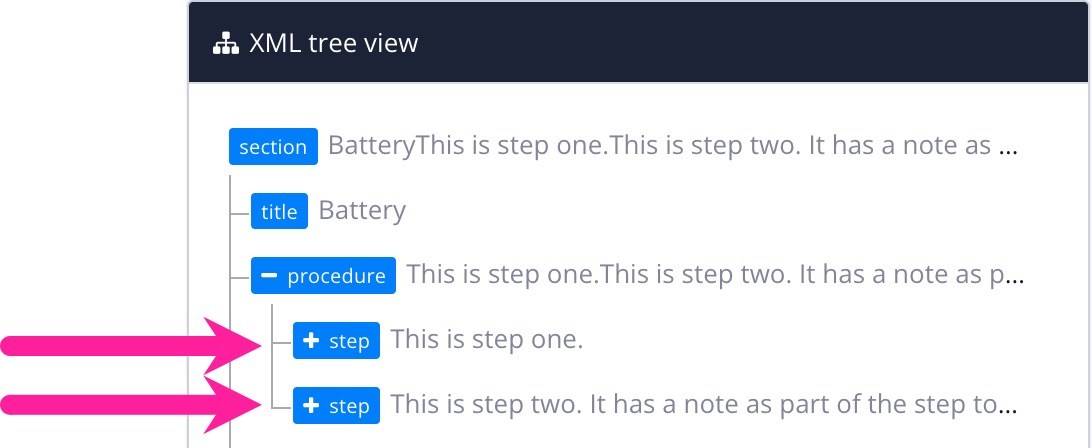

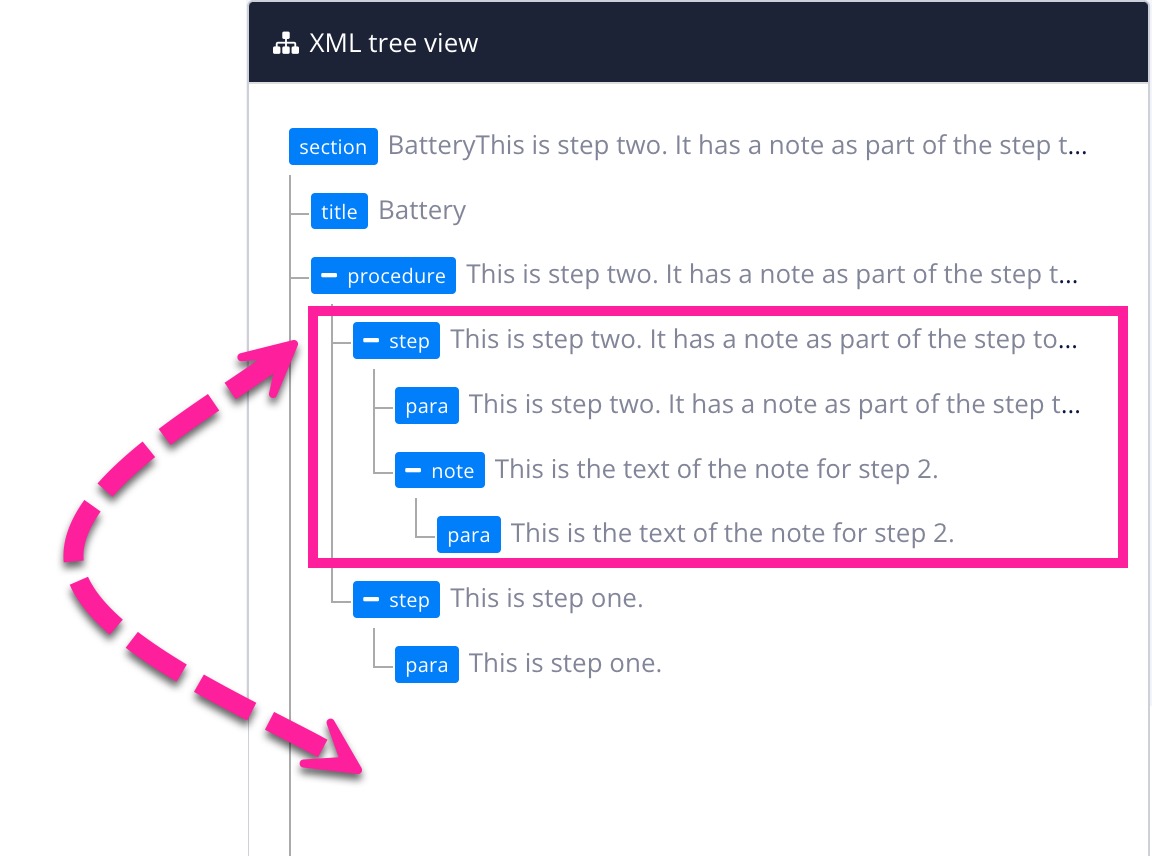

Let's look at a more complex structure, such as a procedure. (This image is taken from the XML Tree View, which is available in the side panel of the main editor. It shows the structure of the topic you are working on).

Here, we can see that the top-level element in the topic is the section. Every topic has a section element at the top, and these are the main "container" in the topic. If you had a topic with subsections, you could have lower-level section elements too (although it is often preferable to insert these as components rather than as sections).

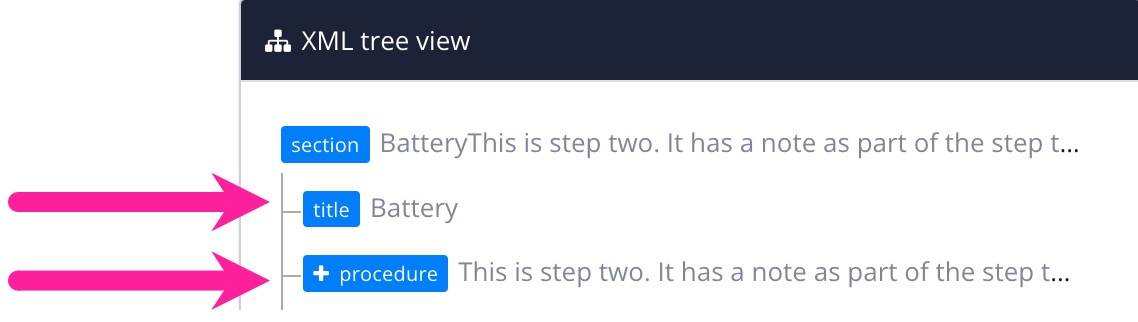

Inside the section, we have all of the other elements. These are also are arranged in a hierarchy. Title is a second-level element and it does not have any other elements inside it (so has no children). Procedure is also a second-level element. It has a plus icon + to show that it is expandable and has elements inside it (its children).

Inside the procedure, there are two steps. The steps are children of the procedure.

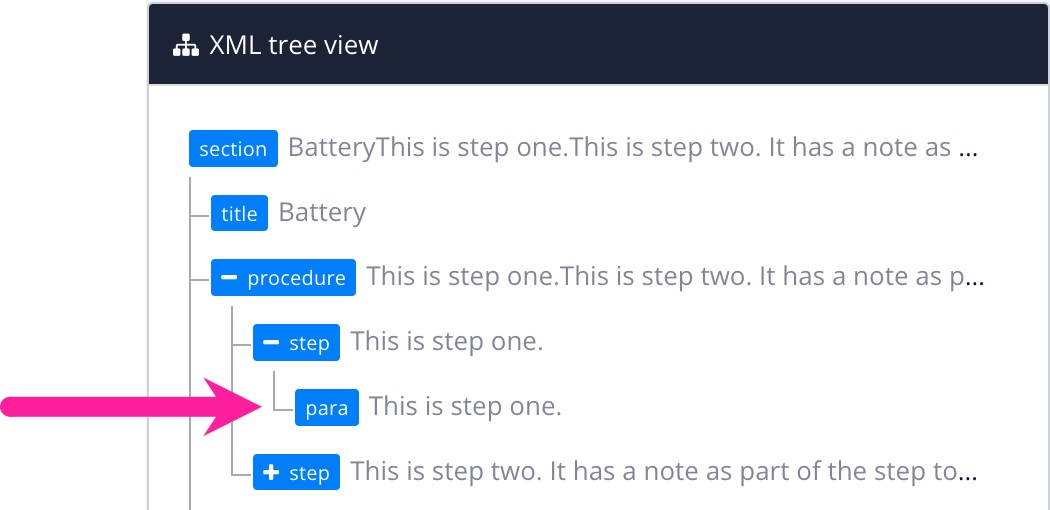

Inside the first step, there is a para. This is a child of the step and a descendant of the procedure.

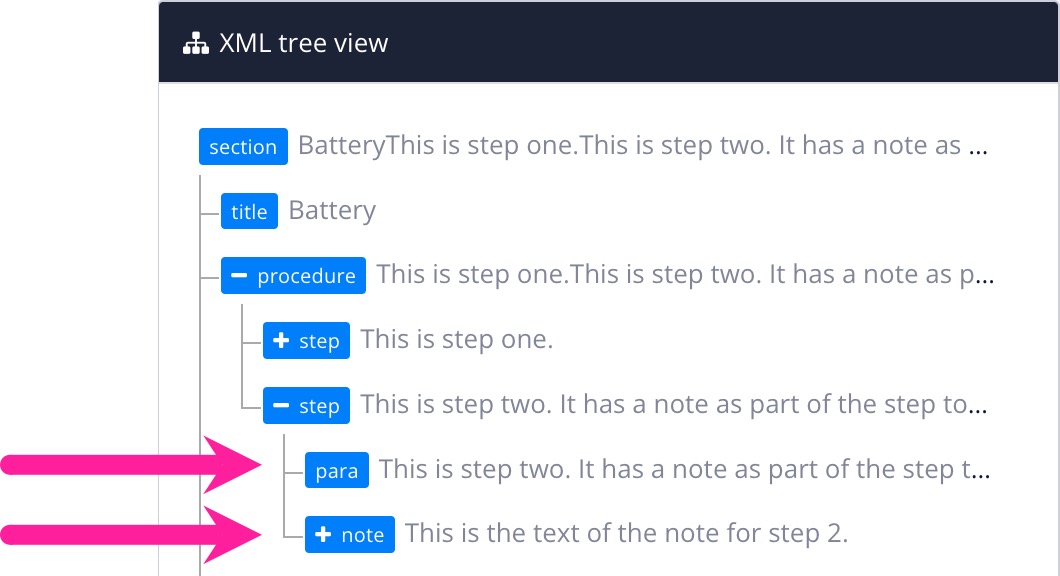

Inside the second step, there is a para and a note. These are children of the second step.

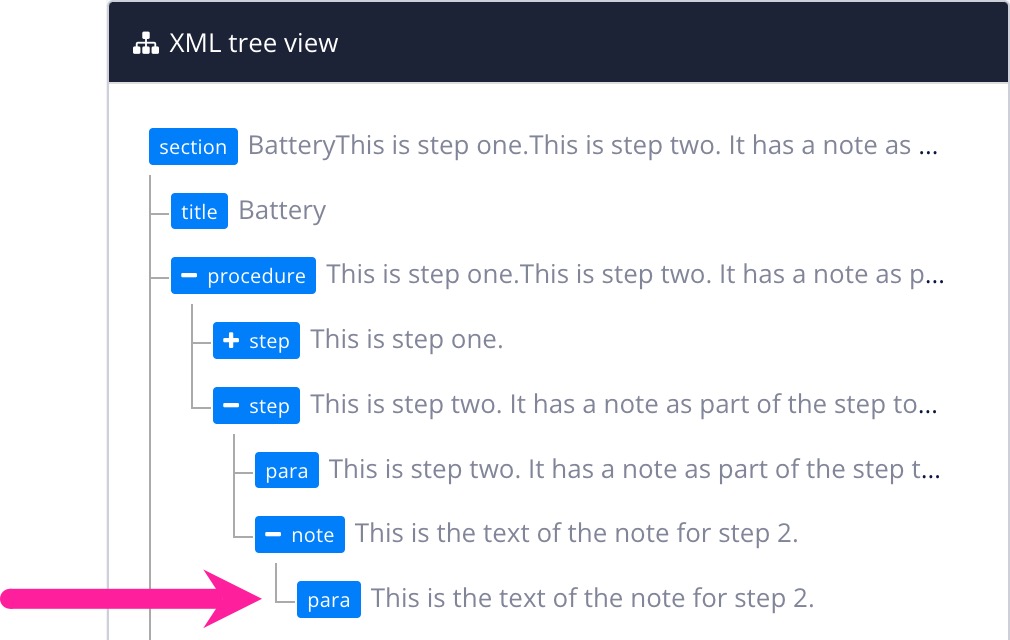

The note also has a para inside it. The note is a parent to this para, and the para is a child of the note. The para is also a descendant (grandchild) of the second step and a descendant (great-grandchild) of the procedure.

When you work with content inside a topic, it is important that you understand that there are parent-child relationships between the different elements. Because when you move, copy, or delete an element, the action applies to its children too.

So if you select the second step and move it above the first, Paligo will:

Move the second

stepabove the firststepin the procedureMove all of the descendants of the second step (children, grandchildren, etc.) as well.

This means you can quickly and easily move, copy, and delete multiple elements or individual elements with a single action.

This is a reference to the most commonly used elements in Paligo. Because Paligo is quite closely based on DocBook, that documentation is referred to at times and can certainly be useful. But this section will describe specifically how some of the most common elements are used in Paligo.

The biggest difference between the Paligo content model and standard DocBook is that Paligo is "topic-based", which means that publications are assembled from small chunks of content ("topics"), rather than built as long "books".

In order to do this, and still stay as close to the DocBook standard as possible, a subset has been used that easily maps to the topic-based model. Therefore, a "publication" in Paligo is mapped to the DocBook article element, and a "topic" in Paligo is mapped to the DocBook section element.

The following are some common general elements and some of them have partly different usage than their counterparts in DocBook. It is usually not necessary to know all about elements to use Paligo. It is meant as a reference and for delving deeper.

This reference is in no way meant to be comprehensive. It primarily describes some of the most common elements, as well as some that specifically differ from the DocBook content model, and it is meant to provide a more digestible reference. For more extensive descriptions and the full list of elements, see the full reference.

Important

Only elements in DocBook lower than article are used in Paligo, so book, part and set are not used.

Tip

For safety messages, see Admonitions.

In Paligo, the article element has been adapted to be used as the Publication component. It is meant mainly to be the structure for reusing topics.

Although slightly differently used in Paligo than in DocBook, it has not been customized to have the name "publication" as an element, in order to stay as close to the open standard DocBook content model as possible.

Although a publication (article) can have a lot of child elements in DocBook, in Paligo there should mainly be metadata in the publication. Usually, this metadata should be in an info element. Note that it has no actual content as child elements. All that is handled in the Structure View in Paligo instead.

<article>

<info>

<title>My Publication</title>

<author>

<orgname>Organization Name</orgname>

<address>

<city>City</city>

<street>Street</street>

<postcode>000000</postcode>

<country>Country</country>

</address>

<email>user@example.com</email>

</author>

</info>

</article>Tip

To learn more, see Publications.

In Paligo, the section element has been adapted to be used as the Topic component. It is meant mainly to be the structure for reusing topics.

Although slightly differently used in Paligo than in DocBook, it has not been customized to have the name "topic" as an element. So the root element in a topic is still called a section, in order to stay as close to the open standard DocBook content model as possible.

Topics (sections) are nested in a publication and can have unbounded depth. Although nesting topics/sections in a publication is the most common, it is also possible to use the section element directly inside a topic as a subsection.

<section>

<title>The Engine</title>

<figure>

<title>Specifications</title>

<mediaobject>

<imageobject>

<imagedata fileref="UUID-f8b27f8c-70ba-83d6-9223-3c1354c98047" width="400" xinfo:image="UUID-f8b27f8c-70ba-83d6-9223-3c1354c98047"/>

</imageobject>

<caption>

<para>The vehicle is powered by a 3.2-litre straight-six engine (X55C33). The performance figures are:</para>

<itemizedlist>

<listitem>

<para>3,246 cc displacements</para>

</listitem>

<listitem>

<para>343 horsepower (256 kW) at 7,900 rpm</para>

</listitem>

<listitem xinfo:product="ACME 2000;ACME 5000">

<para>269 lb·ft (365 N·m) of torque at 4,900 rpm, 8,000 rpm

redline.</para>

</listitem>

<listitem xinfo:product="ACME 1500">

<para>269 lb·ft (365 N·m) of torque at 4,900 rpm, 9,000 rpm redline.</para>

</listitem>

<listitem>

<para>Acceleration to 60 mph (96 km/h) comes in 4.8 seconds. (0-62 mph

/ 100 km/h is 5.0) and top speed is limited electronically to 156 mph (251

km/h)</para>

</listitem>

<listitem>

<para>Output per litre is 95 bhp (80 kW; 108 PS), and power-to-weight

ratio is 9.9 lb/bhp.</para>

</listitem>

</itemizedlist>

</caption>

</mediaobject>

</figure>

</section>

Tip

To learn more, see Topics.

A para is simply a paragraph, probably one of the most used elements.

If you'd like to have a paragraph with a title, the formalpara is also available.

Paragraphs in Paligo differ from DocBook in that they may only contain inline elements. If you add a block element inside a para, it will validate, but as soon as you save Paligo will extract the block element from the para placing it outside the para. This is to optimize the structure for more functionality regarding reuse relations as well as translation.

Tip

To learn more, see Add Elements.

A free-floating heading, such as a lower-level subheading.

Some documents, usually legacy documents, use subheadings that are not tied to the normal sectional hierarchy. Usually in topic-based authoring, you should not create subheadings, but instead let these be automatically created by the nesting structure of the topics in the publication, or simply use section elements within a topic.

If, however, in exceptional cases you need to add subheadings that break the natural heading hierarchy nonetheless, such headings may be represented in with the bridgehead element. You can then use the renderas (read "render as") to set which level heading you want it to represent (with values like "sect1", "sect2", etc).

Tip

To learn more, see Add Elements.

The DocBook element Sidebar has been specialized in Paligo to serve both as a separate component and as a general-purpose reuse wrapper element.

When you add a sidebar as an element in a topic, it works just like in DocBook and becomes a floating sidebar, see Level Text and Image, Create Multi-Columns in Topic (PDF) and Flow Text Around an Image. It is possible to style in the Element Attributes Panel.

When created as an Informal Topic, it will be reusable as a component, but not possible to style, see Create an Informal Topic. Its child elements will appear in output just as if they had been used separately.

There are several types of image elements in Paligo. For full descriptions of these elements, see mediaobject, inlinemediaobject, figure, informalfigure.

mediaobject: the most common element for images. It is both used standalone, as an image where there is no need for a title, e.g insteps. But also for videos, then containing avideoobjectelement.The easiest way to add a video is by using the toolbar icon.

inlinemediaobject: This must always be used inline in text. It is used mainly for small icons and the like. If using the keyboard shortcut for images when inside text, you will automatically get aninlinemediaobject.figure: If you need more infrastructure around your image, such as a title, and perhaps a list or a table that are closely connected to the image, you can use afigure, which will then wrap themediaobject.informalfigure: This is the same as afigure, but with no title.Tip

You can switch between these easily, by toggling the title with the Header icon in the toolbar or using the keyboard shortcut Alt + Shift + H.

<figure><title>The Pythagorean Theorem Illustrated</title>

<mediaobject>

<imageobject>

<imagedata fileref="figures/pythag.png"/>

</imageobject>

</mediaobject>

<caption><para>An illustration of the Pythagorean Theorem</para></caption>

</figure>

Tip

To learn more, see Media.

There are several different types of lists in Paligo. Some of the most common are:

itemizedlist: A list in which each entry is marked with a bullet or similar symbol. Anitemizedlistis also often called "bullet list" or "unordered list". In anitemizedlist, each item of the list is marked with a bullet, dash, or other symbol. Can be used in most block elements (parents). The main child element islistitem. At the top of anitemizedlistmany other elements can be used, however, as in an introduction to theitemizedlist, including an (optional)title,paraand more.<itemizedlist> <para>List of tools:</para> <listitem> <para>Hammer</para> </listitem> <listitem> <para>Screwdriver</para> </listitem> <listitem> <para>Drill</para> </listitem> </itemizedlist>orderedlist: A numbered list. This should usually be distinguished from aprocedure, which is used for instructions / tasks. In anorderedlist, each member of the list is marked with a numeral, letter or other sequential symbol (such as roman numerals). Can be used in most block elements (parents). The main child element islistitem. At the top of anorderedlistmany other elements can be used, however, as in an introduction to theorderedlist, including an (optional)title,paraand more.<orderedlist> <para>List of tools:</para> <listitem> <para>Hammer</para> </listitem> <listitem> <para>Screwdriver</para> </listitem> <listitem> <para>Drill</para> </listitem> </orderedlist>procedure: A list of operations to be performed in a well-defined sequence. Aprocedureis used to write an instruction or a task made up ofsteps (and possibly,substep)s. In most cases it is recommended to use theprocedurelist type rather than a regularorderedlistfor instructions, as it provides several benefits to distinguish between them. There are no explicit elements for pre- and post-conditions (sometimes called pre-requisites or post-requisites) in theprocedureelement in Paligo, just as in DocBook.The model is intentionally simpler, and such elements are avoided. (See this article for more on this: There are no Prerequisites). Instead, they should be described as steps (check the pre-conditions in the first step and the results in the last step). If still really desired, the

taskelement, provides some of this infrastructure, but there is little out-of-the-box styling support for this and it may require a customization. The procedure element is most often used as a direct child to section (i.e the root element of a topic). But it is also valid in many other contexts, so you could for example have a procedure in a table cell, in an example, etc. See the full list of parents here. The main child element isstep. At the top of a procedure many other elements can be used, however, as in an introduction to the procedure, including an (optional)title,paraand more.<procedure> <title>An Example Procedure</title> <step> <para> A Step </para> </step> <step> <para> Another Step </para> <substeps> <step> <para> Substeps can be nested indefinitely deep. </para> </step> </substeps> </step> <step> <para> A Final Step </para> </step> </procedure>simplelist: a list without bullets or numbers. It also has some features like being able to display it horizontally, in several columns, etc.variablelist: a list of terms and definitions.calloutlist: a list of callouts for code listings (programlistingand similar elements)

Tip

To learn more, see Lists and Procedures.

The table type used in Paligo is very similar to an HTML table. You can have a table with or without a title (caption). Without a title the element is called informaltable.

For the most part you do not have to set table attributes manually in the Element attributes widget, as you can do it in the wizard when creating the table, or right-click on the table and open the table properties. But when you do need to add or modify attributes, these are the most common you should know about:

frame: Used to indicate whether there should be a border around the entire table. The most common values are "void" means no border, and "border", which means border on all sides.rules: Used to indicate whether there should be borders between rows and columns. The most common values are "none" or "all".tabstyle: Can be used to create several different table themes in PDF outputs. See Style Tables (PDF) for more information.

For full descriptions of these elements, see table, informaltable.

<table width="100%">

<caption>A table</caption>

<thead>

<tr>

<th colspan="2">

<para>Header spanning both columns</para>

</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>

<para>First cell</para>

</td>

<td>

<para>Second cell</para>

</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

Tip

To learn more, see Tables.

There are two elements for inserting examples in Paligo: example and informalexample. Just like figures and tables, the difference is in having a title or not. By default, an example will just like a figure get a number and a label if it has a title. Example can contain most other block elements.

For more information see example and informalexample.

Tip

To learn more, see Add Elements.

Paligo inherits a very rich set of elements from DocBook for documenting software. This includes elements for GUI components, as well as code snippets and the like. We'll describe some of the most common here.

Tip

To learn more, see Add Elements.

The two most commonly used are programlisting for code blocks and code for inline code snippets inside a para or other textual element.

Code elements preserve line breaks and spacing to represent the code properly. For common output formats like PDF, HTML/HTML5, syntax highlighting and indentation is also available, and can be controlled in the Layout Editor. You can optionally specify the language attribute for a code snippet to specify the programming language represented.

programlisting element looks like://This example is in itself using the programlisting element

//to show the code below

public class Factorial

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{ final int NUM_FACTS = 100;

for(int i = 0; i < NUM_FACTS; i++)

System.out.println( i + "! is " + factorial(i));

}

public static int factorial(int n)

{ int result = 1;

for(int i = 2; i <= n; i++)

result *= i;

return result;

}

}code (inline) element looks like:To show hidden files, type defaults write com.apple.finder AppleShowAllFiles TRUE in the terminal.

Tip

There are several other code elements available, like screen, literallayout, userinput and more. You can explore them in the DocBook documentation following these links.

There are many elements for describing GUI and other software related components as well. These are just a few common examples:

guilabel: an element generally recommended if you want to keep your markup of gui components simple. Use this to mark up buttons, menus and the like.keycap: very useful for marking up keyboard shortcuts. If desired, it can also be wrapped in akeycomboelement to output the delimiter (like a "+" between keys).filename: for file names and paths.guimenu: if you want to be more granular in marking up your GUI components, you can for example use elements likeguimenu, and its sub elements. There are also more related elements likeguibutton,guiiconand so on. Using bothguimenuand the other granular elements can easily become quite complex though. So unless you have very good reason to be that specific, the recommendation is to keep it simple and just distinguish GUI components with theguilabelelement.

There are many more similar elements available, and it's recommended you explore the full reference if you have a need for a very detailed markup for software documentation.

Tip

To learn more, see Add Elements.

The footnote element usually generates a mark (a superscript symbol or number) at the place in the flow of the document in which it occurs. The body of the footnote is then presented elsewhere, typically at the bottom of the page or below a table.

To reference the same footnote several times in a topic, use the footnoteref. To do this, the original footnote needs an xml:id attribute with a unique id. Then in the footnoteref, reference that id with the linkend attribute.

See also footnote and footnoteref.

<informaltable>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Variable</th>

<th>Value</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>foo<footnote xml:id="foo">

<para>A meaningless variable name often used in programming examples</para>

</footnote></td>

<td>5</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>bar<footnoteref linkend="foo"/></td>

<td>3 </td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</informaltable>Tip

To learn more, see Footnotes.